Welcome! And thank you for being here.

Some years back, I was introduced to an old and historical man who I'd been told was responsible for the existence of the poultry industry in South America as part of a 1950s C.I.A. operation. I was sitting at the world's largest dining-room table, eating bland food that the broad-shouldered failure son of the historical man had paid someone to prepare. We all sat in the presence of very many boat paintings and boat encyclopedias, and we drank very, very tannic wines.

In the tradition of this Connecticut family home, I had been separated from the friend who'd invited me, and seated between our red and bulging host and his inarticulate teenage daughter. He hit the table, sweat, and proposed topics for conversation involving Jesus, the Beatles, and the historical accomplishments of his obviously loath and mentally superior father.

All that to say, I was impressed! Through a lot of gnarly ethics, I was hearing the American salesman par excellence, a colonial messenger, the anti-Willy-Lowman (someone I normally identify with in a much more visceral way). But I related to this scary guy in some small way. He had the sincere belief that this humble agricultural product, the chicken, could be a symbol for modern capitalism. Its utility, simplicity, nutrition, and deliciousness served as an argument for a way of life, an economic system. I couldn't help thinking of myself as an agent of some kind of clandestine agency (a nice one!), selling the bonheur of rural France bottle by bottle.

The story I wanted to tell this week begins after a lot of the fun stuff. We've seen the vineyards, we've tasted the wine, we like the labels, and we've made a purchase. The bet is placed and our dutiful task begins. We've got to sell the wine. We've got to justiful this new bottle's journey across an ocean.

How do we introduce a new wine to market? This is a very non-linear attempt at elucidating this process, explaining how and why we bring in this or that wine to our customers.

Any and every imported product lives with an open question as to why all the money and energy was spent to get that product into the states. For all of us normal people avoiding waste, the wine we import has to be not only good, but novel. If a wine that is "close enough" can be found here, the effort should be avoided.

I was reared to believe that ‘good wine’ is analytically ‘terroir wine’. In other words, for all great wine, novelty is an essential aspect. A great wine brings you to a specific time and place. The good stuff is, in this way, self-justifying.

Marco Sferrlazo's (Porta del Vento) Perricone (an endangered variety), from a craggy peak above Camporeal, Sicily is something particular and impossible to reproduce down any mainstreet, USA. But as the quality and diversity of domestic wine goes up, and as the market of beautiful, imported wine expands, the bar starts to get higher and higher for a wine that ethically justifies this journey.

This notion is always heavy on my mind as I'm in the market for new wine. More and more I speak to natural winemakers in Europe who are skeptical of the whole business of exportation. That is, however, unless the European market is in a downswing, which is not at all uncommon lately. Does the need for financial stability eschew all the sustainability concerns of global trade? Surely not. My belief is this: while we try to offer a bigger market share to paysan vignerons, they might be allowed to play by the same rules as the statistically significant offenders of big industry. The message of sustainability, land stewardship, soil health, human health, and the rest... seem worth the same cost as nearly every other imported product in our homes, but and only if we as salesmen can carry that message over the ocean.

Oops, my C.I.A. authorized, liberal incrementalism is showing! Four more years of wine tariffs may proffer one radical solution, but I hope not!

Still, the great majority of these imported wines speak for themselves, and in particular wines that render beautiful their sense of place. As an aesthetic and ethical argument, a wine shows the philosophy of the farmer. It shows his trust in nature, an unvarnished window into a piece of dirt in France. A very cool thing!

From these very epic heights of ethical musing, supping on mostly fermented Pineau D'aunis besides some local paté, a côté du Boeuf cooked all-the-way blue over old vine trimmings, we get right down to the figures -- the fun part for no one.

The price "ex-cellar" is what our winemaker will get for his or her product. This is what we pay for the wine. Even with very thin margins down the line, this number bears a far-away and wispy resemblance to the price our final customer will see on the shelf or on a menu.

Is this wine priced such that a bar can afford to pour is by-the-glass (BTG)? If so, we can order quantities such that one of our partners can work with it in some consistency. Wines BTG move much quicker than wines by-the-bottle (BTB) on wine lists. The vast majority of consumers order wine BTG. Very sad state, that.

Very many of the wineries we work with know this and offer us a range of wines such that we can work with some wines BTG, and some wines BTB. Price and quantity function with the number of accounts we work with, the number of distributors we work with in other states, and how much I want to drink for dinner and other occasions. A Baptism, for example. Or a high-end swap meet.

For the most part, we bring in less than 20 cases of any given wine despite selling wine in 20 states and have a few hundred accounts in New York. So the straight-forward, boring task is to make a map from those 20-odd boxes to some 20 or fewer accounts.

And so the PSYOP begins. This week we announced the arrival of a brand new project from Marc Houtin of La Grange aux Belles. Les Vignes du Fresche replaces Domaine de Fresche, another smallish (~30ha) winery in Anjou that had practiced organic farming and natural winemaking for 20 years. Marc and his new partner Brian Craker, a caviste in Bordeaux, are pushing things forward both in the vines and in the cellar. They eschew chemical treatments completely, are practicing agro-forestry, cutting down on sulphur, installing solar panels, rain catchers, and doing all the important things we like to see as good boys and girls of the green economy.

This is the story we’ll tell in our emails, and reiterate when we taste with our buyers. We’ll do the arithmetic to find the right cuvées for the right accounts. We’ll consider the economics and the style, and where we must, we will spread out the rarest cuvées as equitably as possible.

All this math and thinking are necessary conditions for the rollout, but it’s not sufficient. This is the reason why so many beautiful wines don’t sell. A wine is only well represented in a market when the cellar knows and loves a wine.

Kind of wishy-washy but allow me to illustrate my point with this limerick.

There once was a man who said GodMust think it exceedingly oddIf he finds that this treeContinues to beWhen there is no one about in the Quad.

The response:

Dear sir,Your astonishment’s odd:I am always about in the Quad.And that’s why the treeWill continue to beSince observed byYours faithfully God - Roland Knox

Very cute, and meant to summarize the metaphysics of 18th century scholar George Berkley, who believed that there was no material reality to things like trees or people or golfballs. Instead, the world is nothing but a set of ideas and perceptions, summed up in his little Cartesian dictum, “to be is to be perceived.”

The intuition that a tree keeps on existing when we leave the quad is a strong one, but what about the flavors and personality of a wine? Wine feels more like an idea thing than a substance. We can extoll the virtues of grape varieties, soil types, Stockinger barrels, and long fermentations, but our job as brain washers doesn’t begin until the idea of a wine is clear in our minds. Selling a “crisp Chenin Blanc from schist soils in Anjou,” does almost nothing to satisfy the conditions of a customer looking to place a wine on their list. It describes a substance, which is a gloss on what the wine really is, which is an idea, a creative act.

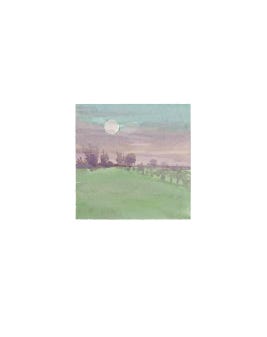

Brin de Lune, the Chenin from Marc and Brian is an argument for naturally made wine in classical proportions. For me, it sometimes has a nostalgic rendering, a wine from a different time.

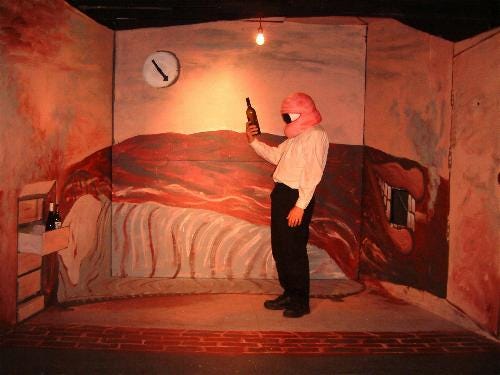

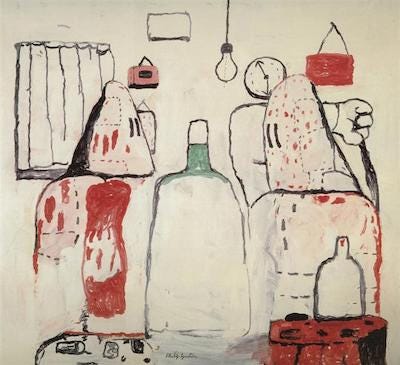

Les Berçantes, Cabernet Franc, isn’t afraid of body and structure, and harkens to a much maligned, Modernist aesthetic.

These are all takes, and thus primarily subjective, but these ideas can be shared and fleshed-out in a way that leads to more and more objective relationships between our ideas. In this way, we can know a wine in a way we can’t know a tree. It’s the same kind of thing that we are, a mental, creative thing.

The critical buyer/taster asks, “why?” with any given taste. The answer can be profound and complex, or simple and beautiful. But always, always, always(!) the wines that we learn to love are the wines that find success in the market, the most diverse homes. Asking yourself, “How can I love this wine?” has been a really powerful position to take in my tasting life. It has opened me up to many awesome things. When I find that relationship to a wine, price, labels, the market… all take a back seat, and I can love Big Brother. Try it at home!

Love,

Steven