Welcome and thank you for being here.

I was blessed to have a wine Christmas in Piacenza, Italy this year, where a friend and colleague gifted me an improbable treasure. The Pentagon is a treatise on agricultural philosophy as it relates to “vine and wine.” It’s a collection of thought from Rainer Zierock, former partner of the famous Elisabetta Foradori and the eponymous winery. In a series of Aphorisms, Zierock develops a kind of symbolic meta-philosophy for thinking about wines and vineyards. The five points of the pentagon are:

Viticulture

Oneology

Soil

Climate

Tradition/Culture

It is a very beautiful book that speaks in metaphor, with very few analytic propositions. For example, the 5 point structure comes from an observed fact that many parts of the grape plant come in fives:

The starting point for the Pentagon is the vine itself. It has so many anatomically pentagonal arrangements that it can be called a pentamerous plant.

Let us take for example:

The blossom:

Around an upper ovary with two carpels and two double Ovules there are:

Five Sepals

Five Petals

Five Stamens or Anthers, and

Five Nectaries.

Five-lobed is the leave of the vine of Vitis vinifera with:

Five principal Veins. -Zeirock, p.51

Something I find very beautiful about the wine world is its disconformity with photography and the moving image. If you’ve seen one glass of wine, you’ve seen them all and it just isn’t any fun to watch the spectacle of slurping and spitting that saturates wine T.V.

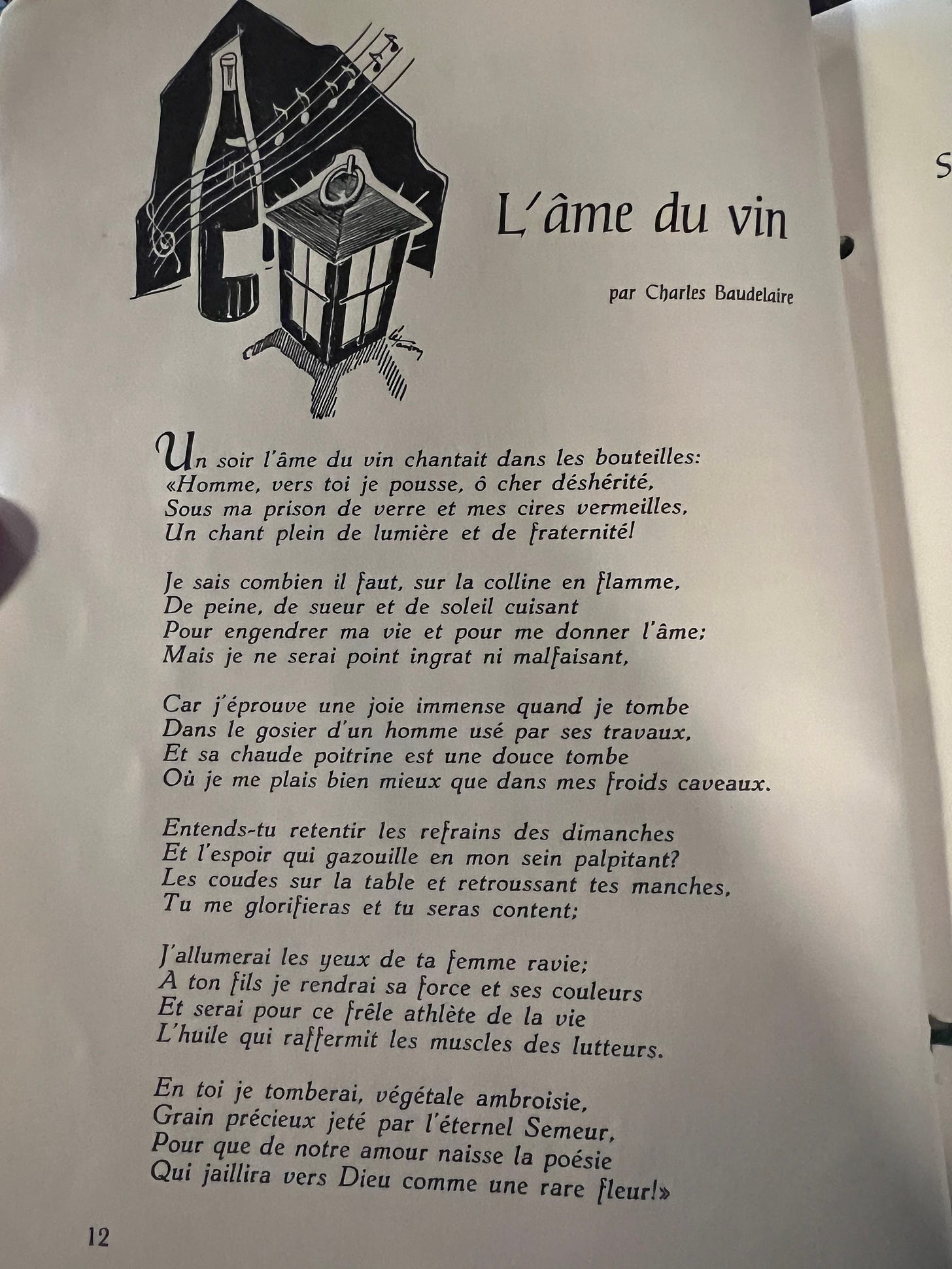

Wine is the ultimate “you had to be there” thing, so films and photographs remove something essential in their naked objectivity. Wine needs a little bit of humanity, a touch of poetry, to be properly represented. Caravaggio’s Bacchus somehow rings truer than any photograph or instagram reel I’ve seen with a glass of wine. Best of all is the ancient genre of wine writing that’s made up of an ocean of metaphors from Pliny the Elder, to Pope Paul III, Goethe, Casanova, Kingsly Amis… There is simply no second place in the devout’s history, except perhaps the ephemeral art of conversation, which is the very reason why wine is so amenable to the written word. Good wine is as conversant as any literate man, but moreover, it is a potion for making good conversation, lauded by Socrates, Napoleon, and Immanuel Kant alike.

The weirdness of its literature is a miracle unto itself. Such strange treatises on the fringes of science, art, religion, agriculture… I doubt there’s a counterfactual world with men and not wine, but for those Rablesian minds who have put pen to paper in the service of fermented grape juice, we seem to be given a pure gift.

The Pentagon is just such a strange yet potentially useful thing. Besides its very scholastic architecture, there are bits of practical wisdom about grape varieties, soil types, and even the use of sulphur! The book is a beautiful thought cloud that kind of floats above all the wine glasses of the world like the angels dancing on the head of a pin.

Can it be the case that this delightful bit of brain entropy was made solely for the extremely rare reader? Who might stumble upon this self-published issue of a few dozen? But, then, for who else?

I’m staying at the apartment of a fellow wine importer, gearing up for this round of wine fairs and it is remarkable how many textbooks and histories and surveys he has got on the subject, and moreover how there is almost zero crossover with the wine books on my shelves. I recognize some familiar spines in Camus, Le Guin, and even some funny philosophy books I’ve also kept around since college, but Vinifications & Classifications vol II? Not so much.

American Wine, Vino, History of Geology, are a unique constellation. Despite titles that suggest an objective permanence, so many wine books are nearly obsolete by the time they are published. They are better thought of as performances, or to use a very disparaging phrase, “works of art.”

While there are certainly some breakthrough classics in the canon, most of the wine folks I know tend to delight in the rarer, obscurantist texts which bear as little relation as possible to our notion of wine today, which bottles matter, and what makes a good wine great. I have a couple of prized possessions in the genre, but none more precious than a couple of tomes from the early 50’s that recount the inauguration of the Luxembourgish wine festival.

I was 22 years old when I first got to visit Europe. I had finished my undergraduate degree in New York, where I was born, and was desperate to find myself anywhere else. A liberal arts program at a fancy university in Manhattan had revealed to me a lot about myself. I was extremely unexperienced and naive next to an army of intelligent, cultured, and boarding school educated young people. It was a very lonely and isolating time that I knew might only be remedied by some radicle change in my perspective. It’s both painful and exhilarating to be the most ignorant person you know, but I sort of became addicted to it and jumped at a really funny opportunity to live in a place I couldn’t find on a map.

Luxembourg was a trip. I got off the plane and tried to find my way to the hotel, speaking my college-level German. Nope, wrong language. They spoke Luxembourgish here. Ever heard of it? Or sometimes French, but rarely German (though they all could. Most of the Luxembougers I know are conversant in all three languages, and also English.). I knew absolutely nothing, and that was an immediate heaven.

My first weekend as a Luxembourgish resident coincided with the annual wine festival. Would that it had been a conference on finance, or some kind of wellness retreat, but no. My personal trip to the European, outer-limits of delight would, of course, take the form of a bacchanal: a mainline of European wine culture at its most piquant and bizarre. It was affecting and I remain intrigued.

I took a bus to a tiny village called Schwebsingen where the fountain at the center of town was drained, covered with ice and stuck with hundreds of bottles of cremant, riesling, and local beers. One was given a glass (it was a rental) and a poker chip to reclaim your deposit for said rental. Why the glass did not suffice as collateral is maybe the first piece of European bureaucratic redundancy I enjoyed. How much could be made collecting abandoned glassware and returning for 5 or 6 euros a pop?

Bottles were sold whole. Glasses were to be shared post-transaction. Flutes clinking the empty rims of clutched, little tasting glasses and the muffled sound of one cork after another was the only noise over the polite hum of a very happy group, speaking an ancient-sounding language I’d heard for the first time maybe 72 hours prior. No music! Just a lot of these beautiful noises and the sing-song cadences of the reddening Burgers.

So many strange scenes would follow that weekend like a fitful night of dreaming. Soon after I arrived, the square filled into a school gymnasium (where I would discover the German/Luxembourg word for High School: ‘Gymnasium’!) A panel of competing, teenage wine queens dressed in glimmering, Lynchian ball-gowns made speeches into microphones which would feed back in their ungodly, fish-bowl-sized wine glasses.

Drunk men in tuxedos grabbed each other tight and danced a kind of sped-up Tarantella. Wine “knights” and elaborately costumed vino-dignitaries from nearby regions paraded around behind coats of arms, carrying bottles of wine and also local wine queens. Adult men and women of means I’ll never know would sleep outside on the hillside vineyards if they weren’t burning the morning hours at the secret 4am spaghetti party championed by said queens.

There is a joy to experiencing novelty, but also a pain in ignorance, or a nausea of uncanniness. I’m very often reminded of a line in We from Soviet dissident Yevgeny Zamyatin,

“To feel one’s self, to be conscious of one’s personality, is the lot of an eye inflamed by a cinder, or an infected finger, or a bad tooth. A healthy eye, or finger, or tooth is not felt. It is non-existent as it were. Is it not clear then, that consciousness of oneself is a sickness?”

Ouch! Still, the point is clear: It is the recursive nature of our lives that makes experience comfortable, predictable, and ultimately intelligible. Our language, our science, our objective reality relies on the recursive essence of our concepts and words. A tree is something wild to behold the first time, and almost nothing to behold the 3,000th time. A scale on the piano is a motor-intellectual feat until it is second nature to the player and happens in an empty way, without a will.

I think the very interesting question we all grapple with at night when we go to sleep, or when we wake up in some totally foreign place, or read some completely life altering novel, is how real or unreal that second nature may be. Is nature itself recursive or is the world constantly something novel that we fit into our comfortable frame.

I know a vigneron who likes to say, following Goethe, “Plants take light and water and make shapes.” A non-recursive picture of nature takes this truth to be a semantic one about a very human concept of ‘plant’, such that if we’re talking about ‘plants’, we just mean those things that make shapes out of light and water.

A 100-year-old grape vine or a 1,000 year old oak tree has been known by an infinity of such names. They’ve been spiritual objects of religious rites, Vitalist mechanisms of biology, Materialist tinder, electromagnetic ground, and everything in-between. Everything and nothing. Maybe nature is like this, like our dreams, where your wife’s head is really a pumpkin but also a jar of hot sauce, but also a poem your aunt wrote and you are your aunt but it’s all happening at Geothe’s house in Penn Station… on and on. In our dreams we can accept all of this. In the morning the patterns are imposed: Coincident (“I swam through that ocean of spaghetti because I was thinking about the secret spaghetti party earlier”), Psychological (“I drove my golf cart into the bubblebath because I felt guilty for…”), Astrological (“Saturn made me do it.”), Sexual (“Whoops, I kissed grandma on the lips again.”), and the like. Stories that make recursive a nature that simply is not.

All the more funny to spill all this ink for something as novel and ephemeral as a glass of wine. Any amateur knows how even one glass of wine to the next, from the same bottle, can make for a remarkably different story. 95 points! we say. 50,000 words on a patch of dirt from the Jura Alpine orogenic wedge! What is the nature of these objects? These stories?

Under the David Bowie interpretation, it all makes for great Martian television. Maybe, up in the clouds, haloed angels in white robes play the harp and read Steiner in a harvest of terrestrial life the way we enjoy the sweet harvest of vegetable life? That’s a romantic notion, but the AI lunatics in my life seem to be making that picture into a concrete reality. These minds, orders of magnitude stronger than ours, can read the world history of wine writing 100 times before I finish typing this word. They might wait 1 million lifetimes between Andrew Jefford typing the word ‘Syrah’ and ‘is’! Now, that’s cool.

But more than cool, it’s a load off! Someone else can figure out the point of all this word soup. Meanwhile, we can enjoy the bizarre novelty that is a story about this or that glass of wine as everything and nothing — a thing we just do. The stranger the better.

Further Reading

Albu, E. (2018). Pliny the Elder, Natural History. In Amsterdam University Press eBooks (pp. 43–48). https://doi.org/10.1515/9781942401223-008

Allhoff, F. (2009). Wine and philosophy: A Symposium on Thinking and Drinking. John Wiley & Sons.

Amis, K. (2010). Everyday drinking: The Distilled Kingsley Amis. Bloomsbury Publishing USA.

Campanale, J., & Stein, J. D. (2022). Vino: The Essential Guide to Real Italian Wine. Clarkson Potter.

De Seingalt Seingalt, J. C. (2018). The Memoirs of Jacques Casanova de Seingalt 1725-1798 Volume 1 Venetian Years. Createspace Independent Publishing Platform.

Lancerio, S., Ferraro, G., & Pallottini, M. (2024). The Wines of Italy judged by Pope Paul III (Farnese) and by his cellarer Sante Lancerio: On the Nature of Wines and the Travels of Paul III. Independently Published.

O’Hara, K. D. (2018). A brief history of Geology. Cambridge University Press.

Pollman, M. (1998). Bottled wisdom: Over 1,000 Spirited Quotations & Anecdotes. Wildstone Media.

Robinson, J., & Murphy, L. (2013). American wine: The Ultimate Companion to the Wines and Wineries of the United States.

Von Goethe, J. W. (1978). Readings in Goethean Science. Biodynamic Farming & Gardening Association.