Every monday at the offices of Steven Graf LLC., I live out my fantasy life as adjunct professor at a small but eagar community college. I wear busted, leather derbies and host "Office Hours" for fledgling somms, shop workers, reps and importers. Here we blind taste wines from far-flung places and well-trodden terroirs alike. It's a round-robin, 20-questions hybrid where the imbibing cadre guesses one after another:

"Is this Pinot Noir?"

"Is this from a hot climate?"

"Is the winemaker in the room with us right now?"

"Steven, where did you get that smart-looking blazer?"

Nearly always, the first question is this one: "Is the wine French?"

When the blinder says, "No," There is usually a collective groan, cries of "Oh God!"

What they are bemoaning is a guessing game outside of the prim and polished AOC system of France where grapes like Harslevelu, Pignoletto, and Delaware exist; In the terroirs of Liguria or the German Ahr. As a Francophone in my own right, I feel a sympathy for my beleaguered tipplers. Thus, apropos of nothing, I present to you a Francophone Guide to Italy. May it serve you where your bearings are low, where your taster is wanting, and where the price of pleasure is a soupçon of knowledge.

I. Grapes

What with our uniquely American fixation on race, it might be news to you that the overwhelming majority of wine grapes (red, white, and otherwise) are all from one species of vine: vitis vinifera. It has become a custom here in the new world to categorize wines by the grapes that make them, so let's start with some Italian wines made from french varieties. They come in basically two categories: The first are historical plantings from northern areas that hosted french merchants who sold seeds and clippings of varieties like Pinot Noir, Chardonnay, Pinot Gris (griggio), and Pinot Blanc. Like squirrels hiding nuts for the winter, many of these forgotten interlopers have taken root in the identity of these northern regions.

The other case is a more modern version of cultural diffusion most epitomized by the "Super-Tuscan" revolution of the 80s and 90s. These are international varieties (see, French), looking to appeal to the American palate under the influence of the "Wine Spectator" years.

Wine 1.1

Elizabetta Montesissa's plots of Syrah are new plantings of a variety that has grown and thrived in the young soils of Emilia Romagna since before Betta, her father, or grandfather can remember. The vines are rooted in a pleistocene-era beach, which today is covered with 3 and 4 million-year-old oyster shells. As soil goes, 3 or 4 million years is quite young, turns out. For instance, all the surrounding bedrock is over 300 million years old.

The wine is Rio Fratta, 100% Syrah from limstone soils, pressed, fermented and left completely alone to be what its phenotype wants it to be. The result is a wine that even the most craven Syrah freaks will experience with a sense of shock and revelation at this rustic and baudy interpretation. Unlike her neighbors/cousins in the northern Rhône, Rio Fratta does something a lot of Italian wines can do with these indigenously French varieties. It is unabashedly varietal. High notes strike the back of the eyes with eucalyptus, pine, tomato water, and blood. The bass is bacon, smoke, mushrooms, baked apples, stewed blueberries, and old books. There is a managery of Syrah-stuff in-between, for to which the bold may stare into the soul of a thing that, too often, is treated with kid gloves.

(Pretty cool? I'm biased as I sell these wines for a living. Don't trust me? Try "Rio Stoppa" from the same region, from a blend of french varieties, of which much of all of these ideas apply.)

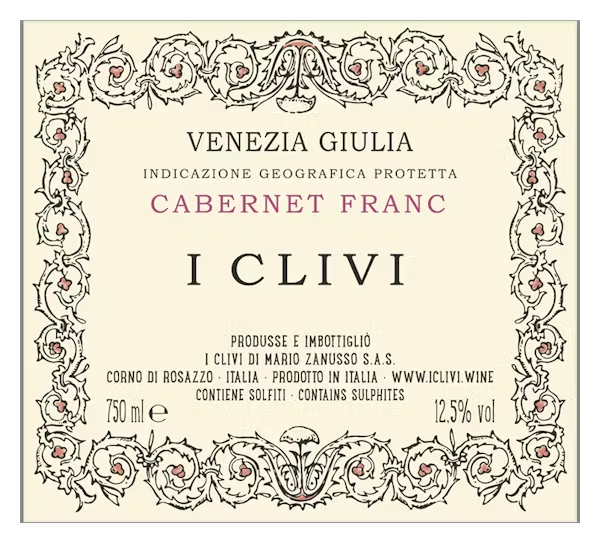

Wine 1.2

In a sense, this Cabernet Franc from Venice performs a similar task. Where the cabs of Chinon and Bourgieul can be as green, stony and angular as the great chateaus of the middle centuries, this wine tastes like, ahem, fruit. It's important to remember that these French varieties in Italy are growing in a climate thousands of miles south of their native homes, so ripeness is much easier here and that heat is often felt in the fruit of the wine.

Here I'm sort of reminded of the difference between some new wave coffee and "coffee coffee." In some new wave and natural productions, producers will let coffee beans ferment with some or all of the beans’ fruit still in place. Coffee coffee, as I'm told they say in the biz, removes all the fruit before fermenting and roasting. The bones are the same, the phenolic structure is all there, but the extra fruit in new wave coffee gives a bright and juicy dynamic to the experience that I think is relevant to this very modern, drinkable style of Cabernet. This extra bit of juice generalizes over many such cases, particularly so in the natural wine world. Hard to find an easier pleasure than a bottle like this.

Wine 1.3

Tunia "Cantomoro" Cab Sauvignon

I don't pretend to know too much about Super Tuscans despite my subjection to countless bottles of arbitrary Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot from Italy, sitting around bowls of Ragu with brothers and cousins on Long Island (not a bad pairing!). Most of those tasted like cheap Montepulciano and nothing. You can find these bottles anywhere. They are heavy, have regal Italian names, and display their French varieties prominently on the front label.

But! And this will be the last one, we work with an amazing pair of friends in Arezzo, Chianti, who make a very beautiful Cabernet that drives both of our aforementioned points home. The phenolic character of the Cabernet is at its most profound and dense. The fruit springs from the glass and buzzes on the palate like a confection. For this reason, Tunia and many other winemakers in Italy hold their wines back for many years in order for these bombastic flavors to integrate. After 10 years, mostly in a very large barrel for micro-oxygenation, the sharp tannins are saturated with flavor and the fruit has stewed and rasinated like a fine amaro. The energy comes from the structure and autumnal cornucopia.

2. Place

Some winemakers are real terroir-heads and make a lot of tiny differences in soil composition, exposition, the way the wind is trapped by this or that hill, etc. Others are less convinced. I recall a very prominent, natural wine legend on the Mosel feeling kind of disappointed that his riesling from the flat vineyards was more or less the same quality as the riesling from the steepest, more dramatic slopes. But lucky you, intrepid francophone, who can taste the dirt rainbow yourself and decide.

The next wines are all from terroirs that bear some significant similarity to some other famous terroirs in France. A lot of these wines are also made with French grapes, which is obviously no mistake, but I tried to pick wines that very transparently show you their provenance -- some aspect of the soil or whatever.

Wine 2.1

This fantastic Syrah from Cortona bears little resemblance to the Syrah from Elisabetta Montesissa or the haphazard vineyards elsewhere in Tuscany. Unlike the majority of those plantings, which are from very young soil of the ancient seabed, the silk, clay and humus here are a few hundred million years older, and (more importantly) remarkably similar to the soils you find in the Rhône where Syrah is king.

Stefano's Syrah is remarkably elegant and Modern in style. It does not share the rusticity of its Italian counterparts, nor the phenolic digressions. Here, black olives shine with some bright blueberry fruit a blinder might easily mistake for Cornas or St. Joseph. It is an international wine made with the subtlety and intellect that has beguiled collectors of Syrah in the Northern Rhône for generations, but with a natural technique rooted in biodynamics and radical non-interventionism. It makes for one of the more friendly and pleasing wines in recent memory.

Wine 2.2

Davide Xodo TAI ROSSO 2023

This wine is made in the Vicenza region of the Veneto, which is one of the most important wine regions in Italy, producing everything from Prosecco to Amarone. Yes, it is a region that shares a lot of wine grapes with France, but it is also a facsimile for many different microclimates in France. Lot's of Northern Italy is covered in mountains, but Vicenza is basically flat, with a few hills and so it is protected from rain by the Alps. It is thus a very dry region rich in limestone, and baked in sun.

I'm reminded of a few different, lesser celebrated places in France with poor soils and dry climates, like parts of Anjou and Saumur, Bugey, or the Macon. Mostly you see these decomposed sedimentary soils and limestone in flat parts of Languedoc between the Pyrenees and the Mediterranean Sea. But in all of these places, you see a penchant for semi-carbonic wines with lots of amazing primary fruit. Tai Rosso is a local name for grenache which, in this wine, gives bright strawberry at the outset, but finishes with salt and minerals proper to this natural and easy-going style. It would delight in any Parisien wine bar.

Wine 2.3

Pavese e Figli 2020 Blanc de Morgex et de Salle

Valle d'Aosta is a wine region squarely in the Italian Alps and this stunningly crisp yet complex wine comes from some of the very highest vineyards in Europe. Depending on where you are on the mountainside, you can have more or less sand, and more or less limestone. This cuvée comes from very poor soil with nearly no topsoil, and thus the wine is very subtle in terms of fruit or acidity, while all its structure and charm come from a stony mineral character, and the memory of a very cold and crisp place.

For those, like me, who are enchanted by the low acid, yet brilliantly gleaming wines of the Savoie and Haut-Savoie, these vineyards are the Italian version. The grape, Prié blanc, contributes the slightest bit of fattiness to an austere pleasure of cold, mountain springwater. It is elegant, subtle and as beautiful as the place where it was made.

3. Culture

Finally, in discovering wines from a new part of the world, there is not always a one-to-one comparison to place or variety so you have to look to fashion, style, or cultural resonance, in that order of importance. There are a number of very superficial fashions in wine that pop up in France and Italy and elsewhere. If you see a self-described Pet Nat in Italy (not Frizzante!), you can be sure that you're in for a wine styled after Mosse's Mossamousettes or something like it. The aforementioned Super-Tuscan style has become remarkably popular among the American Collector class, as has the Barolo from French Barrique. These are styles of winemaking that reflect a generational or critical period, and may point to more than fashion but are less meaningful than cultural or philosophically aligned wines that share an intellectual approach to winemaking that is born out of tradition and reason. Perhaps the great Spumante of Italy and Champagne bear this kind of resemblance. They are deep and meaningful cultural methods that are shared across borders. These are the most interesting comparisons to focus on.

Wine 3.1

As an imbiber raised in what I like to call the “Chenin Generation,” this bottle of Fiano cracked open a whole new world of Italian wine for me outside of macerations and bubbles. This is a reductive, white wine. Crisp, clean, and racing with acidity. Very similar to a Loire Valley Chenin, deep and wooly.

More and more, white wine of this style seems to be the standard-bearer for wine folks in the know, particularly those who are allergic to "orange wine" in all its guises. This wine is as elegant and crystalline as anything in France. As southern climates are concerned, Fiano is maybe an n of 1, and no better represented than this small, 3 hectare estate.

Wine 3.2

For the natties out here, we have a beautiful example of a wine culture dedicated to easy, simple, nonchalance. We are in the land-locked region of Umbria, where Sangiovese can be rustic and tannic, but in the hands of Carlo Tamborini, is a pink ray of delight. A short carbonic maceration brings out a color of light watermelon juice. Think Tavel, or the chilled reds of the Jura.

This wine isn't just a simple carbonic ferment either. Its minerality is remarkably complex, structuring the character of this noble variety in a way that sings on the pallet. This is natural wine of yore, at its very best and happiest.

Wine 3.3

Cascina Pugnane Barolo Bussia 2018

In truth, you may choose from any number of Barolo or Barbaresco producers here: Roagna, Fabeo Gea, Produttori, Sandri... the fact is that the idea of Barolo as your parents know it, is a modern invention. A few hundred years ago, these Piedmontese vineyards were making sparkling wines and macerations like everyone else in this region. And while the French Barrique of the Barolo boys may be a bit of Winespectator fashion, the botti style of still Nebbiolo is here to stay and thank goodness. For all the burgundy hounds out there, Piedmont offers another dimension of a very familiar thing. Transparency, grace, structure, fruit, and, most of all, typicity. Lifetimes are spent comparing vintages and vineyards in a more than worthy pursuit of analytical deftness and wines of true terroir.

So, while we've only given a slight gloss of a few wonderful wines to get you started, I hope you can use this as a little guide to start looking at the wines of Italy though a new lens, taking what you know from the didactic AOC system of France, and maybe using some of that knowledge to find new and life-changing wines in a place that's just a big less relegated to conceptual boxes.